The Inside Story: Finding the Area of a Circle

Learning why this formula “works” can help you understand math at a deeper level, building your skills for school and tests.

It might surprise you to know that the core of mathematics has nothing to do with equations or computations. Mathematical thinking is all about observing patterns and imagining abstract objects. Mathematicians are story-tellers, and the stories they write reveal truths about these mathematical objects. Consider a circle, for example. You might know that the area of a circle is , but do you know why? As mathematician and teacher Paul Lockhart writes, “it is the story that matters, not just the ending.”

Here we present three stories or “proofs” to demonstrate why the area of a circle is . All of these explanations depend at some level on the knowledge that the circumference of a circle is . Where does come from? By definition, is the ratio between the circumference and the diameter () of a circle. So, the fact that the circumference of a circle is is really just another way to state the definition of . On the other hand, the formula for a circle’s area isn’t self-evident and requires more convincing.

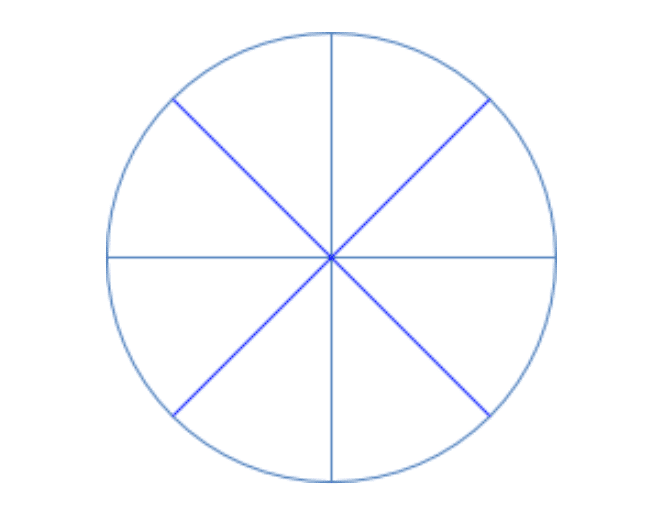

Story 1: Rearranging Sectors

Divide your circle into some number (more than 2) of equally sized slices. In the image below, we’ve divided it into eight slices.

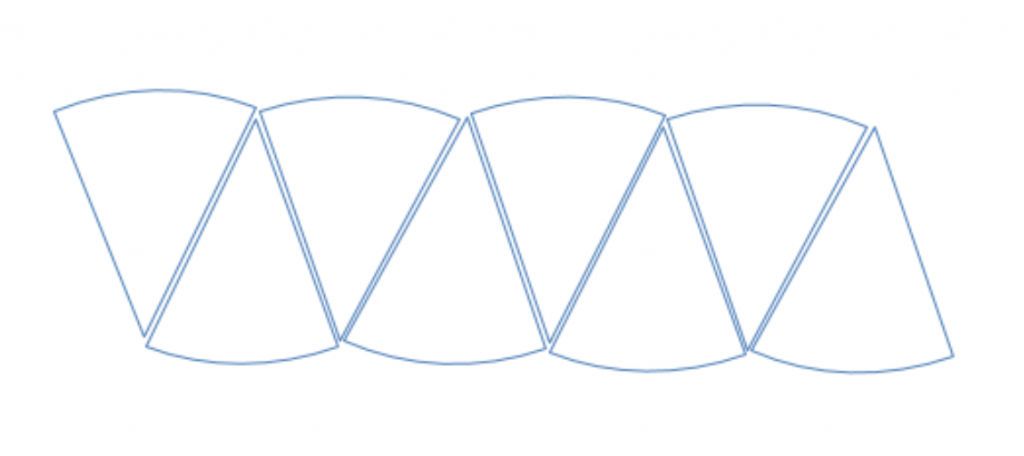

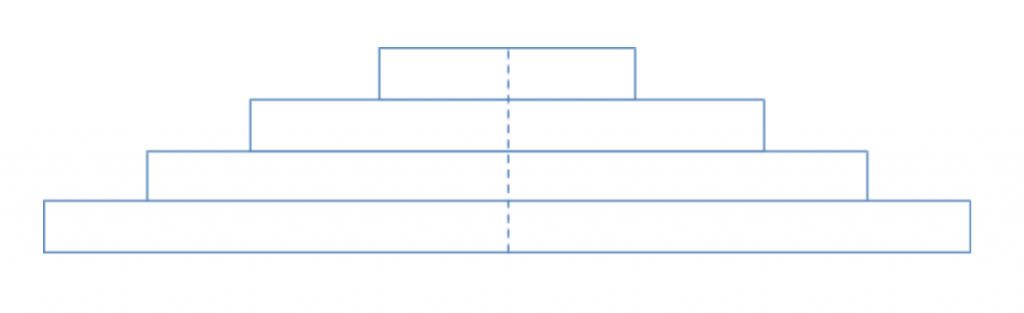

These slices can be rearranged so that the resulting shape resembles a parallelogram, as depicted below. You can think of it as a parallelogram with two “bumpy” sides. Note that we can do this no matter how many slices we cut, as long as they are equal in size.

The height of this parallelogram is the radius of the circle, and one of its bumpy sides has length that is half of the circumference of the circle, i.e. . If we do this same procedure with even thinner slices, such as dividing a circle into 20 or 50 wedges, we will see that the bumpiness will start to flatten out, and the overall shape will trend towards a parallelogram with area . Taking more slices doesn’t change the overall area, so we see that the area of the circle that the slices came from should also be .

Story 2: Rearranging Rings

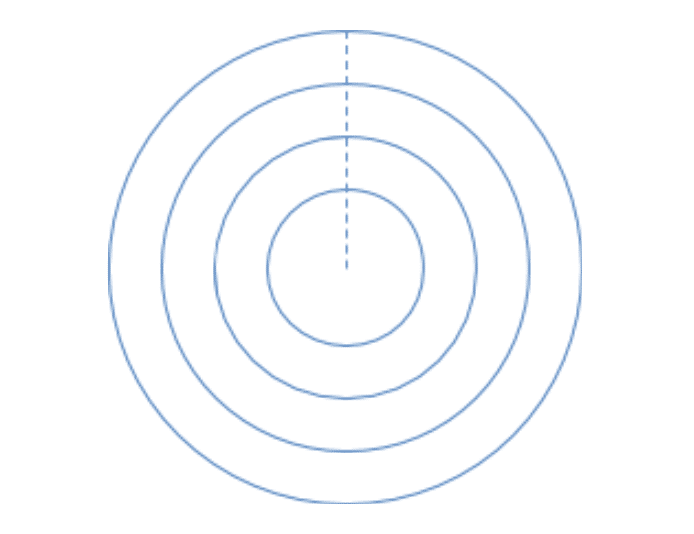

This explanation is kind of similar to the previous one, but instead of cutting the circle into slices like a pie, we’re going to cut it into concentric rings like a tree.

If we cut down the dotted line and unroll the concentric rings so that their rounded edges lie flat we get a shape like a jagged triangle:

This shape has a height that is the radius of the circle, and its base has a length that is the circumference of the circle . If we take more and more slices and follow this same procedure, the rings will get thinner and thinner and our resulting shape will look more and more like a triangle with area . Since the area of the “triangle” is the same as the area of the circle, we see that our circle must also have area .

Story 3: Approximating Polygons

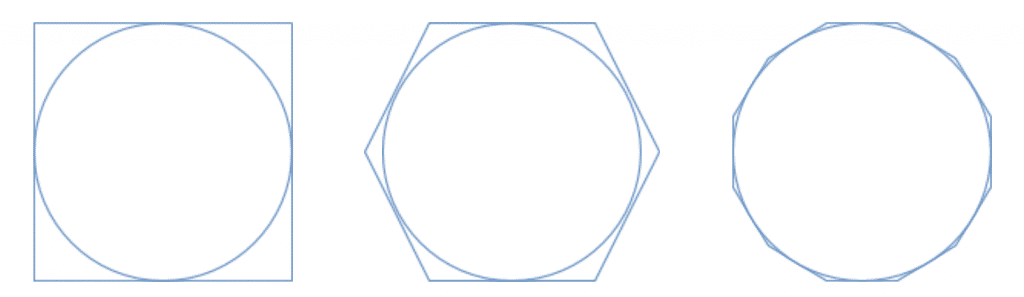

We know we can inscribe a circle into regular polygons. Notice that as the number of sides of the polygon gets larger, it starts to look more and more like a circle. You could also say that the area of the polygon that isn’t covered by the circle will get smaller and smaller. For example:

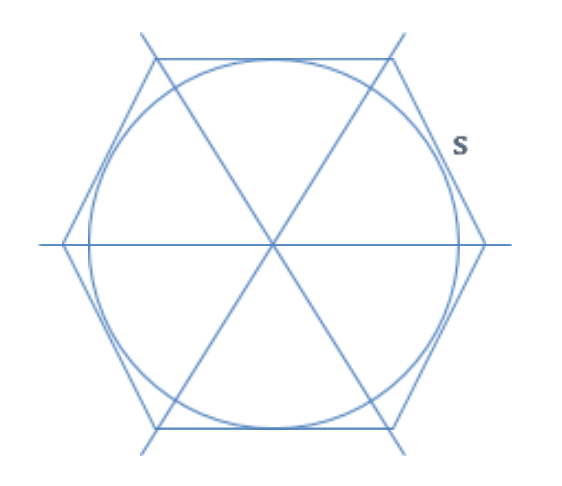

We can calculate the area of a regular polygon by dividing it into triangles. For example, with the hexagon:

We can see that the hexagon is made of six congruent, isosceles triangles, with height and one side whose length we will call . The area of each triangle is thus . So, the area of the hexagon is . Notice that is actually half of the circumference of the hexagon.

Now, if we do this procedure for an arbitrary -gon (i.e. a polygon with sides) with circumference , we will get the area of the polygon is . And, as we look at polygons with more and more sides, these polygons start to look more and more like circles, so will get closer and closer to the circumference of the circle and will get closer and closer to the area of the circle. So, we can think of the circle as a sort of “infinite-sided -gon” with area

So there you have it! Three “stories” that demonstrate why the area of the circle is . And in fact, there are many, many other ways to tell this story. Personally, I find the “why” of math to be pretty magical. That said, it is also useful to understand these things. You’re much more likely to remember formulas if you understand where they come from, and building up your logical thinking skills will help you perform better in school and on standardized tests like the SAT.

For more math insights, check out our blogs on common algebra mistakes (part 1 and part 2).